21 November, 2012

Authentically Plastic?

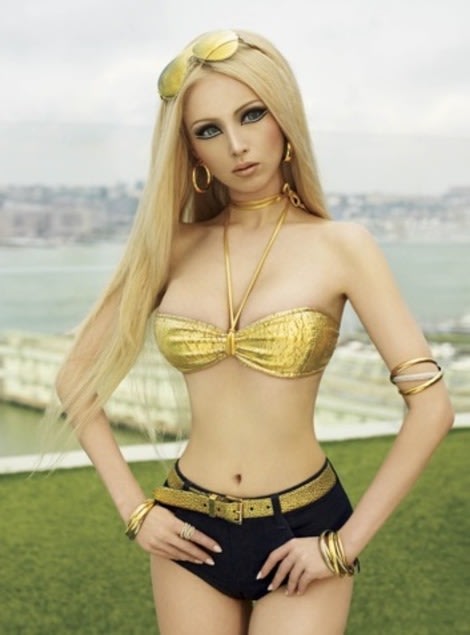

Images of and stories about this "human Barbie" have been floating around the internet for a few weeks now, but today on the quality news source Yahoo!, this article considers to what extent the individual in question used plastic surgery or Photoshop to achieve the "Barbie" look. I have discussed women falling into the Uncanny Valley before, but what I find notable about this story is not at all that a Russian model wants to look like a doll. As the Yahoo! article itself says, Valeria Lukyanova is neither the first nor the only human Barbie in the world. Interesting to me is the fact that there is somehow a difference between the falsity of makeup (a minor, hardly noteworthy one), and the falsity of computer or surgical manipulation (much more fake!). The article accuses Lukyanova of "possibly manipulating the public in the process" of showing the world her Barbie-ness, apparently because she claims to have had no plastic surgery, though "experts" are sure that she has. Perhaps her insistence has something to do with common claims that no real woman could match Mattel's Barbie's proportions. At any rate, I am led to consider the difference between "honest" artistic embellishment (makeup, airbrushing, contacts) and "fraudulent" bodily manipulation (Photoshop or plastic surgery). Does it matter which Lukyanova has undergone in order to look more like a piece of plastic? And if it does matter, why does it matter? Is your "fake" different from my "fake?" Are both different from Lukyanova's?

04 October, 2012

The Science of Fraud

Two stories caught my attention in the past week or so, both about fraud in the scientific community. The first is this story about Annie Dookhan, who seems to be the major reason for " a burgeoning investigation that has already led to the shutdown of the lab, the resignation of the state's public health commissioner and the release of more than a dozen drug defendants." In addition to pretending to have a Master's degree from the University of Massachusetts, Dookhan now admits to having faked the majority of her tests for a Massachusetts state lab, most of which involved criminal narcotics testing. Perhaps thousands of accused were wrongfully convicted in the nine years in which Dookhan worked there. The article explains the situation better than I have, but makes only a feeble attempt to discover why Dookhan might have committed such comprehensive fraud, other than that she "wanted to be seen as a good worker."

The other story involves a larger fraud trend in the scientific community; according to a new study, fully two thirds of retractions of biomedical papers are due to fraud or suspected fraud. The study divides types of scientific misconduct into "fraud or suspected fraud (43 percent), duplicate publication (14 percent), and plagiarism (10 percent)." The report suspects that many other instances of fraud may go undetected to bring the numbers even higher.

The stories are not particularly distinct from others I have read, I suppose. It's quite possible that it was simply harder to detect scientific misconduct in 1975 than it is now, and that it has not actually increased "tenfold" as the study suggests. Annie Dookhan may be one of a series of impostors whose purposes for fraudulence will never be determined to anyone's satisfaction. I am struck by them, perhaps, because I still labor under the delusion that science is more objective, more factual than other disciplines. The forger of scientific data must be more brazen even than the literary forger, because he knows that someone will almost certainly check his data. In fact, Dookhan got around those checks by committing yet another fraud and signing others' names to her work. Does the fraud count on the scientific community to be lazier than he even is, or is his pressure to publish so great that he is scared and rushed into sending work out that is either not tested or not his own? Are similar trends happening in humanities publications, or is this type of misconduct not as possible there?

The other story involves a larger fraud trend in the scientific community; according to a new study, fully two thirds of retractions of biomedical papers are due to fraud or suspected fraud. The study divides types of scientific misconduct into "fraud or suspected fraud (43 percent), duplicate publication (14 percent), and plagiarism (10 percent)." The report suspects that many other instances of fraud may go undetected to bring the numbers even higher.

The stories are not particularly distinct from others I have read, I suppose. It's quite possible that it was simply harder to detect scientific misconduct in 1975 than it is now, and that it has not actually increased "tenfold" as the study suggests. Annie Dookhan may be one of a series of impostors whose purposes for fraudulence will never be determined to anyone's satisfaction. I am struck by them, perhaps, because I still labor under the delusion that science is more objective, more factual than other disciplines. The forger of scientific data must be more brazen even than the literary forger, because he knows that someone will almost certainly check his data. In fact, Dookhan got around those checks by committing yet another fraud and signing others' names to her work. Does the fraud count on the scientific community to be lazier than he even is, or is his pressure to publish so great that he is scared and rushed into sending work out that is either not tested or not his own? Are similar trends happening in humanities publications, or is this type of misconduct not as possible there?

29 August, 2012

Reviews and (Dis)Honesty

I bought a new car this summer, and before I had even signed the paperwork I was told that when the customer survey arrives I should try to give the seller "all 5s," and that if I couldn't, I should talk to him first to explain why. The ostensible reason to talk to the seller is so that he can improve on his performances in future, but my guess is that it is actually to guilt the buyer into giving the seller all 5s, either so she doesn't have to talk to the seller again, or because she is convinced that to not give him that score would be somehow unfair to him. I passively aggressively refused to complete the survey, despite at least semi-weekly requests to do so. I do feel a bit rude, but "if you can't say anything nice, say nothing at all," as they say.

In the world of internet book publishing, the customer review may be even more important than the silly auto survey I won't do. With the demise of both physical book stores and newspaper literary review columns, one must either magically come upon a book after an Amazon or Google search, or see some sort of online review of it in order to purchase and read it. The online review has become all pervasive--I can review not just my favorite (and least favorite) book, but my bank, bowling alley, and Brazilian restaurant with little effort. These items and places want me to review them, and they sometimes even give incentives for it.

Of course, no one is supposed to buy favorable reviews, because money makes people do things they might not otherwise, like lie, saying they had the best meal ever when it was actually lukewarm and bland. Of course, just because no one is supposed to doesn't mean no one does. A recent NYT article discusses just this subject: a man started a business in which he sold favorable book reviews, often multiple reviews for the same book, to fledgling authors who wanted to become noticed online in order for their books to sell. Some authors purchased the service saying they didn't need the reviews to be positive, but most expected to buy positive reviews. The author explains that

Consumer reviews are powerful because, unlike old-style advertising and marketing, they offer the illusion of truth. They purport to be testimonials of real people, even though some are bought and sold just like everything else on the commercial Internet.

We know that advertising exists to sell us a product, and most of us can see the falsehoods in claims advertisements make. A review, on the other hand, is not created by a marketer and is not automatically positive, so we are doubly swayed when we see a positive review. A problem arises, though, when the reviews are not only falsely positive but also based upon nothing; Todd Rutherford appears to have fabricated reviews for clients of books he had not read, in essence scamming both the consumer and his client. Rutherford explains that “Objective consumers who purchase a book based on positive reviews will end up posting negative reviews if the work is not good,” but he apparently has no problem selling those objective consumers the bad book in the first place. We've all read a bad book, and few will go hungry over the cost of that book, but I think I might feel rather betrayed by a terrible book with overwhelmingly positive reviews.

In the world of internet book publishing, the customer review may be even more important than the silly auto survey I won't do. With the demise of both physical book stores and newspaper literary review columns, one must either magically come upon a book after an Amazon or Google search, or see some sort of online review of it in order to purchase and read it. The online review has become all pervasive--I can review not just my favorite (and least favorite) book, but my bank, bowling alley, and Brazilian restaurant with little effort. These items and places want me to review them, and they sometimes even give incentives for it.

Of course, no one is supposed to buy favorable reviews, because money makes people do things they might not otherwise, like lie, saying they had the best meal ever when it was actually lukewarm and bland. Of course, just because no one is supposed to doesn't mean no one does. A recent NYT article discusses just this subject: a man started a business in which he sold favorable book reviews, often multiple reviews for the same book, to fledgling authors who wanted to become noticed online in order for their books to sell. Some authors purchased the service saying they didn't need the reviews to be positive, but most expected to buy positive reviews. The author explains that

Consumer reviews are powerful because, unlike old-style advertising and marketing, they offer the illusion of truth. They purport to be testimonials of real people, even though some are bought and sold just like everything else on the commercial Internet.

We know that advertising exists to sell us a product, and most of us can see the falsehoods in claims advertisements make. A review, on the other hand, is not created by a marketer and is not automatically positive, so we are doubly swayed when we see a positive review. A problem arises, though, when the reviews are not only falsely positive but also based upon nothing; Todd Rutherford appears to have fabricated reviews for clients of books he had not read, in essence scamming both the consumer and his client. Rutherford explains that “Objective consumers who purchase a book based on positive reviews will end up posting negative reviews if the work is not good,” but he apparently has no problem selling those objective consumers the bad book in the first place. We've all read a bad book, and few will go hungry over the cost of that book, but I think I might feel rather betrayed by a terrible book with overwhelmingly positive reviews.

17 August, 2012

Plagiarist Suspended!

According to this article, renowned columnist and public intellectual Fareed Zakaria has been suspended from Time and CNN after it was discovered that several of his recent pieces are stolen from others. Discuss!

16 August, 2012

Faking Your Death: Harder than it Used to Be?

I have no statistics on rates of success with faking one's death for insurance money and/or to escape debt, but a recent story suggests that it may not be too easy these days. A New York man, apparently aided by his son, went "missing" off of Jones beach two weeks ago but was located a few days later when he was issued a speeding ticket in South Carolina. It sounds as though the scheme may have been half-baked, but with today's surveillance and electronic tracking methods, far more elaborate preparations would be necessary than this man and his son evidently made.

I'm reminded of a film I watched (pictured above), in which a man (played by the always satisfyingly creepy Anthony Perkins) miraculously and secretly survives a plane crash for which he has purchased flight insurance and terrorizes his estranged wife (Sophia Loren) until she agrees to fraudulently collect the insurance money and split it with him to be rid of him forever. In this case, a man simply faked his death because the opportunity presented itself; he used luck to his advantage and was (nearly) successful in acquiring the insurance money. It is surprisingly easy for Sophia Loren to collect it; further, Anthony Perkins can presumably chuck his passport and live incognito in Europe. Raymond Roth is probably a desperate idiot, but I can't help but wonder if he could have disappeared off Jones Beach if he had lived fifty years ago.

17 February, 2012

On (Creative) (Non)-Fiction and Accurate Facts

In this article from Slate Magazine, Dan Kois reviews the book The Lifespan of a Fact, which involves the fact-checking of an essay written by John D'Agata and includes the essay, the comments by the fact-checker, and D'Agata's responses to the fact-checker (Jim Fingal). As if the book itself weren't confusing enough, Kois includes his own story about meeting Tim O'Brien in this review, and subsequently fact-checks the review here. Although the majority of Kois's review seems to imply that D'Agata is a jerk for fudging facts to suit the aesthetics of his essays, his own fudging of facts in his review suggests that the exact truth is undesirable in a creative essay, if not impossible. Kois takes both sides in the argument for truth in non-fiction, and leaves his reader (or at least this reader) suspicious of all authors' veracity, not simply that of D'Agata.

D'Agata's argument in terms of his essay's lack of truth is that "it's called art, dickhead," but why write in a nonfiction genre and then make things up? Why was it important for Kois to pretend he had interviewed D'Agata and Fingal rather than simply read their book? I understand that the non-fiction writer wants to arrive at a particular, perhaps essential, truth with his essay, but changing the facts in order to point to this truth seems to me to undermine everything. Furthermore, what's the point of having a fact-checker at all if you simply don't plan to write facts in your work? People want to read essays and memoirs because they purport to tell true stories, amazing or poignant or moralizing, but true. No one's preventing D'Agata from writing fiction about teen suicide and tae kwon do, and this type of realistic fiction would certainly sell. Maybe these little manipulations of fact don't matter, but if not, why manipulate facts at all?

D'Agata's argument in terms of his essay's lack of truth is that "it's called art, dickhead," but why write in a nonfiction genre and then make things up? Why was it important for Kois to pretend he had interviewed D'Agata and Fingal rather than simply read their book? I understand that the non-fiction writer wants to arrive at a particular, perhaps essential, truth with his essay, but changing the facts in order to point to this truth seems to me to undermine everything. Furthermore, what's the point of having a fact-checker at all if you simply don't plan to write facts in your work? People want to read essays and memoirs because they purport to tell true stories, amazing or poignant or moralizing, but true. No one's preventing D'Agata from writing fiction about teen suicide and tae kwon do, and this type of realistic fiction would certainly sell. Maybe these little manipulations of fact don't matter, but if not, why manipulate facts at all?

10 February, 2012

Translation and Truth

I've been thinking a lot about translation lately, perhaps because I've been reading a lot of fiction translated from other languages (mostly French). Several times in the class in which the translated work was read, we have glanced over or mostly ignored the problems that must arise when this highly stylized experimental French or Italian fiction is rendered into English. A Spanish language edition of William Gaddis's Carpenter's Gothic has also just been announced and reviewed, and this translation of one of my favorite authors into a language I also (mostly) read makes me further consider the necessity of and problems with fiction and poetry translation. I have no doubt that translators are extremely skilled and often brilliant to be able to capture the ideas of any writer in a language not his own, but are they often brilliantly inventing their own works of art?

Italo Calvino's If On a Winter's Night a Traveler somewhat whimsically tackles some issues that arise with translations. In the novel, you, the Reader, read parts of almost a dozen different novels translated from various languages in search of the ending to If On a Winter's Night a Traveler. The enigmatic "translator" of the novel, Ermes Marana, is the character who could perhaps best be called its villain because he produces fraudulent and unauthorized translations of books with no apparent concern about their authenticity whatsoever. This character is an abuser of both good faith and ignorance, but is he also the closest of all of the novel's characters to being its true author? As the fringe groups searching for him ask, is there an absolutely true Ur-text, or an absolutely false one, and what's the difference? Furthermore, what am I to do with the fact that the entire novel has been further translated for me to consume?

Italo Calvino's If On a Winter's Night a Traveler somewhat whimsically tackles some issues that arise with translations. In the novel, you, the Reader, read parts of almost a dozen different novels translated from various languages in search of the ending to If On a Winter's Night a Traveler. The enigmatic "translator" of the novel, Ermes Marana, is the character who could perhaps best be called its villain because he produces fraudulent and unauthorized translations of books with no apparent concern about their authenticity whatsoever. This character is an abuser of both good faith and ignorance, but is he also the closest of all of the novel's characters to being its true author? As the fringe groups searching for him ask, is there an absolutely true Ur-text, or an absolutely false one, and what's the difference? Furthermore, what am I to do with the fact that the entire novel has been further translated for me to consume?

03 February, 2012

As Good as We Pretend to Be

A few days ago, this story appeared on Yahoo! (and very likely elsewhere), about a senior admissions official at Claremont McKenna College who has been falsifying SAT score reports to U.S. News and World Report and other places for several years. The inflation of scores was apparently not extreme (10-20 points), but may have increased the liberal arts college's desirability and (perhaps) ranking among other colleges, leading to increased revenue for the school. The official has resigned and the school has launched a formal investigation.

Though not as severe, the case is reminiscent of the Atlanta Public School scandal that unfolded last summer, when it was revealed that "at least 178 teachers and principals in Atlanta Public Schools cheated to raise student scores on high-stakes standardized tests." One wonders what kind of incentive students have to do well, when officials will fudge things to make both themselves and the students look better. In both cases the cause probably involves money, but there also seems to be a sense, at least in the Atlanta case, that the teachers were acting for what they believed to be positive ends. I won't start the argument about the (legitimate/illegitimate/high/low/) importance of standardized testing in secondary school, but all of this does seem a lot of time wasted that could have been spent actually teaching students. Perhaps no one attended Claremont McKenna because of its students' test scores, but the school will certainly have the stain of dishonesty on it for several years now.

Though not as severe, the case is reminiscent of the Atlanta Public School scandal that unfolded last summer, when it was revealed that "at least 178 teachers and principals in Atlanta Public Schools cheated to raise student scores on high-stakes standardized tests." One wonders what kind of incentive students have to do well, when officials will fudge things to make both themselves and the students look better. In both cases the cause probably involves money, but there also seems to be a sense, at least in the Atlanta case, that the teachers were acting for what they believed to be positive ends. I won't start the argument about the (legitimate/illegitimate/high/low/) importance of standardized testing in secondary school, but all of this does seem a lot of time wasted that could have been spent actually teaching students. Perhaps no one attended Claremont McKenna because of its students' test scores, but the school will certainly have the stain of dishonesty on it for several years now.

05 January, 2012

Quentin Rowan and the Pathology of a Plagiarist

The story of Quentin Rowan, serial plagiarist, is now several months old, but as I was mired in Mark Twain and Frederic Jameson a few months ago, I will discuss it now! The story is as follows: Rowan, slowly rising to success as a poem and short story writer, published the spy novel The Assassin of Secrets in late 2011 with the reputed Little, Brown company. A few days after its publication, readers (including novelist Jeremy Dun) began to see significant similarities between it and several published spy novels. The Huffington Post has an excellent synopsis of the story here. After a brief silence on the subject, Rowan revealed all in a "Confession" where he describes plagiarism as an "addiction" and (sort of) explains why he did it. He says that plagiarism was a substitution for his earlier alcoholism, and encourages the public to see plagiarism "if not as a disease, at least as something pathological."

Rowan's confession is fairly persuasive in its buildup of pathos ("I first tried to get sober when I was 18") and insistence that he confessed to the plagiarism right away once caught (as though one can successfully deny it). I will not call him the names that he says others have called him, but I am suspicious of the addiction explanation he gives. Perhaps I don't understand addiction pathology, so I cannot begin to see how alcoholism would translate into stealing writing from others (literary kleptomania?). However, I do know that there is very little in the way of apology to Rowan's victims: not the authors whose works he stole, not the publishing company, and not his apparently savvy readers. I suppose it's great that he wrote a confession, but shouldn't there also be some contrition?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)